| Tue. May 06, 2025 |

|

|

||

|

||||

| ||||

By Dr. Muzammil Ahad Dar and Dr. Shahnawaz Qadri

Introduction

Sustainable development is a multifaceted concept that aims to balance economic growth with environmental preservation and social wellbeing. Maintaining real disposable income of an economy ensuring long-term sustainability of natural, human, and social capital is at its core. Public goods and global commons play a crucial role in this process. Effective environmental management is essential, yet requires a comprehensive approach, interconnecting policy regulation, economic incentives, community engagement, and technological innovation-GIS and Satellite monitoring. We draw on Costa Rica’s comprehensive National Payment for Environmental Services (PES) Program and Kenya’s Mara Elephant Project (MEP). Market-based mechanisms help incentivize tradable resources and disincentivizes anti-environmental activities.

Sustainable Development:

Sustainable development implies real disposable income of an economy, usually measured in real Net Domestic Product (NDP). NDP should common’s be either constant or increasing over a period of time. For a constant NDP, the total capital stock of an economy (i.e., total productive assets), has to be maintained on a long-term basis which consists of man-made capital (e.g., built infrastructure, machines, technology, etc.), natural capital (e.g., forests, biodiversity, water resources, etc.), human capital (e.g., education, skills, knowledge, etc.) and social capital (e.g., culture).

Natural capital generates services or benefits—called ecosystem benefits—which is treated as income to the economy. In a developing economy like India, income from natural capital plays a crucial role in reducing poverty and enhancing livelihoods of majority low-income people. Empirical studies show people in forest-dependent states like Madhya Pradesh earn a significant amount of their household income from forest ecosystem services.

Examples of natural capital include Norway’s REDD+ programs and Ecotourism Revenue. Studies in developing countries show rather than ‘income growth’, improvement of natural capital (e.g. GDP vs. NAC) drives people’s welfare on long-term basis.[i]

Types of Environmental Resources: Public and Private Goods:

Environmental resources can be classified into four types: a) Public Goods; b) Private Goods; c) Common Pool Resources; and d) Common Property Resources, categorized by two criteria: excludability and subtractability. Public goods are non-excludable and non-subtractable i.e., marginal cost of excluding a consumer is high but providing services to one more consumer incurs zero cost. Non-subtractability implies consuming a good or service does not diminish its use-ability. Many environmental goods/services are public goods (e.g., carbon sequestration providing services globally without exclusion. However, because public goods are unrestricted, resources are depleted without sustainable management. In contrast private goods are excludable and subtractable. Unlike public goods, the cost of excluding consumers from private goods is negligible.

Common Pool Resources:

Common pool resources possess non-excludability and subtractability include ‘global commons’ such as deep sea fisheries, atmosphere, the ozone layer, and biodiversity. Since excluding potential exploiters is extremely difficult global commons experience subtractability. Hardin predicted profit-maximizing individuals would over-exploit global commons leading to extinction events.[ii] Cooperation for limited-use will avoid resources extinction, but fear that others will not cooperate encourages non-cooperative behavior that leads to overexploitation. Hardin described this phenomena as ‘tragedy of the commons’, including GHG emissions and atmospheric pollution. A vulnerable global commons threatens natural, human and social capital.

Box-1: Prisoner’s Dilemma and Tragedy of the Commons:

The tragedy of the commons can be explicated through prisoner’s dilemma wherein two suspects (X and Y) for murder are offered choices with possible punishments: if both confess only 6 year jail (-6X, -6Y); If only one confesses then 10-year jail (0X, -10Y) or (0Y, -10X). If neither confess, both still get one year (-1X, -1Y). The payoffs are given in the matrix below:

|

Individual X ?

Individual Y ? |

Confess |

Does not Confess |

|

Confess |

(-6, -6) |

(0, -10) |

|

Does not Confess |

(-10, 0) |

(-1,-1) |

A possible strategy would be to minimize negative utility of the jail term? Like ‘mutual silence’ (-1, -1), however, due to uncertainty about the each other's behavior, confession becomes the safest choice. Tragedy of the commons follows; if everybody cooperates natural resources will sustain, but international situation warrants non-cooperation over cooperation.

Common Property Resources:

Common property resources (CPRs) possess excludability and non-subtractability. CPRs like are usually managed community groups locally. The property rights over CPRs are usually communal. Community rules stipulate sharing equitably avoids subtractability. Elinor Ostrom documented various cases to demonstrate how communities across the world manage CPRs together.

Ecosystem Services of the Environment:

Environmental resources generate different ecosystem services classified into four major categories: a) Provisioning Services; b) Regulating Services; c) Cultural Services; and d) Supporting Services. The ecosystem services generated by wetlands offer all four types of ecosystem services. Table-1 shows examples of wetland services.

Table- 1: Wetland Ecosystem Services

|

Ecosystem Services |

Examples |

|

Food

Fresh Water Fiber and Fuel Biochemical Genetic Materials |

Fish Production, wild game, fruits, grains

Storage and retention of water for multi-use

Logs Production, fuel-wood, fodder

Medicines and other materials from biota

Genes for resistance to plant pathogens, ornamental species, etc. |

|

Climate regulation

Water regulation (hydrological flows) Water purification and waste treatment Erosion regulation |

Source of and sink for greenhouse gases; influence local and regional temperature, precipitation, etc. Groundwater recharge/discharge

Retention, recovery, and removal of excess nutrients and pollutants Retention of soils, sediments |

|

Natural Hazard

Pollination |

Flood control, Storm protection, etc.

Habitat for pollinators |

|

III-Cultural Services: |

|

|

Spiritual and inspirational

Recreational Aesthetic Educational |

Source of inspiration; Wetland signify spiritualism and religious values Opportunities for recreational activities

Aesthetic value in aspects of wetland ecosystems

Opportunities for formal and informal education and training |

|

|

|

|

Soil Formation

Nutrient cycling |

Sediment retention; accumulation of organic matter Storage, recycling, processing |

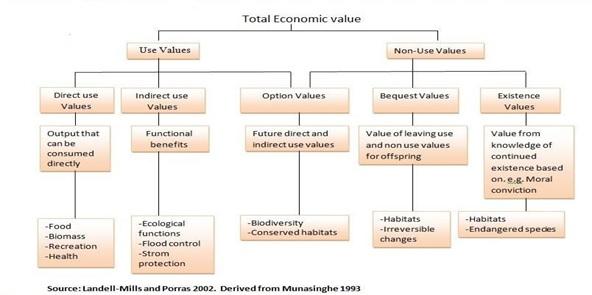

Environmental economists define ecosystem services in a different way which include values and benefits but not in conventional classification. They introduced the TEV (Total Economic Value) concept, containing both use-values and non-use values (or passive use). Use value means consuming by direct physical interaction or indirect physical interaction while as non-use values may be ‘willingness to pay to conserve/preserve wetlands (see-Table-2).

Non-use values combined with use values substantially enhance the TEV of the environment. Unlike market goods such as soft drinks, most of the ecosystem values are not traded in the market, for example, cultural services provided by the environment.. The environmental values are highly valuable but there is no market price for them. Policy-makers often ignore the importance of ecosystem services sustaining human welfare.[i] Neglect of the resources leaves them more vulnerable to negative externalities and destroy resources in the long-run.

Externalities:

Different ecosystem values involve externalities which occur when one person’s production or consumption affects another’s. Externalities are either positive or negative depending upon the effects they brought in the consumption or production activity. Imagine two neighboring farmers, one cultivating sunflowers, and the other beekeeping. This would lead to positive externalities. The honey output will increase due to sunflower plantation, while bees nearby increase sunflowers production. Negative externalities have adverse effects: For example, groundwater use by one farmer may reduce consumability for other farmers. Alternatively, consumption of fossil fuels that emit greenhouse gases adversely affects the welfare of people in other countries. The potential hazards of extinction of public goods invites local or government’s intervention like local forestry programs, conservation zones a sort of shared goods. More stringent policies would entail privatization of public goods.

Internalizing Externalities:

Externalities arise due to market failures. Consider, a leather handbag production causes water pollution affecting wetland. Suppose the market price of leather bag is Rs. 3000 per unit which covers a marginal cost used in production process including owner’s profit. If we assume loss of ecosystem services caused by leather bag production equals economic value of Rs. 4000 will be an external cost of producing bag. However, market price (Rs. 3000) does not add external cost reflect a complete market failure. Adding external cost would raise the price to Rs. 7000, discourage leather bag demand and control the damage to socially desirable level. Inclusion of external cost to leather bag price internalizes negative externality.

Pigouvian Solution:

If externalities are not internalized, as the above market failure suggest, goods generating positive externalities become under-provided and goods generating negative externalities over-provided. In positive externalities, suppose, a farmer cultivates tree crop on 20 acres and her increasing of cultivation say to 30 acres would generates more ecosystem services and social benefits. However based on marginal private cost and private benefit she finds no incentives for increasing cultivation that increases the social benefits because costs of increasing exceed private benefits. This is a market failure and can be corrected by internalizing positive externality: adding estimated marginal benefits to the society and marginal costs. Provision of marginal benefits, additional cost compensation, such as a subsidy, encourages farmer’s investment in positive farming[ii], maximize social benefits and correct market failure. Conversely, in negative externalities, farming which harms ecosystem services (and therefore human welfare) should be discouraged.

Coasian Solution:

Ronald Coase argued that most environmental problems are due to ill-defined property rights over natural resources. As the atmosphere is a shared public resource, atmospheric pollution has become a major issue in the ‘tragedy of the commons. Coase suggested assigning property rights to users will facilitate negotiations between owners. Based on the Coasian approach, many countries have devised tradable pollution permits to control air and water pollution. Carbon trading is another Coasian approach to mitigate GHG emissions.

Managing Global Commons:

The tragedy of the commons in the fishing sector is addressed using a tradable permit system. Permits allow for quotas and quota transfer systems (Individual Transferable Quotas (ITCs). Each EU country follows ‘fishing practices’ as mandated by the Common Fisheries Policy . The tragedy of the commons in the groundwater sector can be addressed through taxing over-extraction (e.g., Pigouvian tax) and banning borewells in over-exploited areas.

Since the dominant strategy of the Prisoner’s Dilemma prevails for all of the countries emitting GHGs, International Governmental Organisations like UN and IPCC role ought to facilitate cooperation. Introducing measures related to the Coasian Solution, Pigouvian tax, mutualizing property rights, sharing common use of resources; eco-friendly tradable goods, and conferring entitlements may enable protective and sustainable use.

Managing global commons requires a ‘PRI’ approach:

- Promoting-positive externalities through incentives like Payments for Ecosystem Services (e.g., Costa Rica’s reforestation subsidies) and renewable energy tax breaks, aligning private gains with public benefits;

- Removing-negative externalities via regulatory tools such as carbon pricing (EU ETS) and Pigouvian taxes (Norway’s €80/ton CO? levy), internalizing hidden environmental costs; and

- Fostering cooperation through transboundary agreements (Paris Accord) and community-led governance (Nepal’s forests), ensuring equitable decision-making and trust. Together, these strategies—rooted in the PRI framework (Promote, Remove, Initiate)—address market failures and fragmented governance, balancing economic growth with the preservation of natural, human, and social capital for intergenerational equity.

Dr. Muzammil Ahad Dar is Assistant Professor at Kumaraguru College of Liberal Arts and Science, India; Dr. Shahnawaz Qadri is Assistant Professor at University of Kashmir.

[i] Examples of natural capital include Norway’s REDD+ programs (forest conservation incentives) and ecotourism revenue (e.g., Kenya’s Maasai Mara). Studies in developing countries, such as India’s forest-dependent regions, show that enhancing natural capital accounting (NAC)—which values ecosystems like clean water and pollination—drives long-term welfare more effectively than GDP-focused growth. For instance, Nepal’s community-managed forests reduced rural poverty by prioritizing NAC, ensuring resources for future generations, while GDP often neglects ecological health.

[ii] Common pool resources (CPRs), characterized by non-excludability and subtractability, include ‘global commons’ such as deep-sea fisheries, the atmosphere, the ozone layer, and biodiversity. Due to the difficulty of excluding potential exploiters, these resources face subtractability, where overuse depletes their availability. Garrett Hardin’s seminal 1968 essay, The Tragedy of the Commons, argued that profit-maximizing individuals, acting independently, would inevitably over-exploit shared resources, leading to ecological collapse (e.g., overfishing, GHG emissions). Hardin posited that without centralized regulation or privatization, cooperation to limit use would fail due to distrust—a dynamic akin to the Prisoner’s Dilemma.

However, Elinor Ostrom’s groundbreaking work challenged this thesis. In her 1990 book Governing the Commons, Ostrom demonstrated that communities can sustainably manage CPRs through collective governance, trust-building, and locally tailored institutions, as seen in Nepal’s community forests and Japan’s irrigation systems. While Hardin’s framework remains influential for global challenges like climate change (where centralized coordination is lacking), Ostrom’s research underscores that cooperative solutions are possible when stakeholders have equitable decision-making power.

Thus, while Hardin’s “tragedy” persists in contexts like atmospheric pollution (a global commons with fragmented governance), Ostrom’s insights highlight pathways to avoid resource extinction through shared entitlements and reciprocity.

Garrett Hardin’s seminal essay “The Tragedy of the Commons” was originally published in 1968 (Science journal, DOI:10.1126/science.162.3859.1243).

[iii] Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005) – Establishes the TEV framework and underscores the non-market nature of ecosystem services.

TEEB (The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity, 2010) – Highlights policy failures in valuing ecosystem services.

[iv] Provision of marginal benefits, such as subsidies or cost compensation, encourages farmers to invest in positive farming—defined as agricultural practices that generate positive externalities (societal benefits beyond private gains). Examples include agroforestry (integrating trees with crops to enhance biodiversity), organic farming (avoiding synthetic chemicals to protect soil and water quality), or planting pollinator-friendly habitats (boosting crop yields and ecosystem resilience). These practices not only improve farm productivity but also deliver public goods like carbon sequestration, reduced erosion, and cleaner waterways. By compensating farmers for these additional societal benefits, subsidies align private incentives with public welfare, correcting market failures where the true value of ecosystem services is undervalued. Conversely, farming practices causing negative externalities (e.g., monocropping with chemical runoff that pollutes rivers) harm ecosystem services and human welfare, warranting disincentives like taxes or regulations to internalize hidden costs

| Comments in Chronological order (0 total comments) | |

| Report Abuse |

| Contact Us | About Us | Donate | Terms & Conditions |

|

All Rights Reserved. Copyright 2002 - 2025